COP25 has just concluded, and despite another extended negotiation session, the progress made was far from satisfactory. The main controversy still revolves around Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, concerning the establishment of a global carbon market and how to determine globally recognized accounting rules for carbon reductions (to avoid double counting, among other issues). These contentious issues have been repeatedly delayed, with hopes seemingly pinned on time to resolve everything. Jennifer Morgan, Executive Director of Greenpeace International, noted that 2019 was a year of unprecedented climate impacts, and the conference's underwhelming outcomes pale in comparison to the rapid effects of climate change. "The final resolution does not reflect the urgency required by science to address climate change, fails to respond to the needs of people affected by climate change, and does not ensure the environmental integrity of the Paris Agreement. The overall situation of global climate action is facing serious challenges," said Jennifer Morgan.

The UN Climate Change Conference has now held its 25th session, and the negotiation process has generally been very inefficient. Historically, successful climate negotiations have largely depended on major powers reaching basic agreements before the conference. For the negotiations themselves, the climate conferences seem more like a formality. Expecting national negotiators to reach consensus and conclusions in just two weeks of noisy discussions is unrealistic. This requires pre-conference consensus between major interest groups, such as joint statements between China and the US, China and Europe, and the BASIC countries. Bilateral cooperation among key players is the foundation for multilateral consensus.

It's like a project collaboration where if the top leaders haven't agreed on the project framework and budget, expecting technicians to negotiate and finalize the agreement is virtually impossible. From the current negotiations, it seems that they bring more negative and pessimistic information. Each year, the climate conference gathers tens of thousands of people from all corners of the globe, which is both labor-intensive and costly, with a significant carbon footprint. Nowadays, the UN Climate Conference seems more like a party show, a platform for businesses and civil society organizations, which holds greater significance in this regard.

The Influence of the UN Climate Conference

The UN Climate Conference has always been a sacred event in the realm of environmental and low-carbon issues, where participants feel they are part of a mission to save the Earth and humanity. During my student days, I dreamed of attending the UN Climate Conference and contributing to this noble cause, which would certainly broaden my international perspective.

I first learned about COP in 2009 when I naively applied to attend the Copenhagen Climate Conference but couldn't make it due to various reasons. Later, thanks to the selection by the British Embassy's Cultural and Educational Section and the support of Cathy, I finally attended the UN Climate Conference. In 2012, I stayed in Doha with Jianchao from Aob Environmental and Wilson in Singapore during COP18, experiencing a "tough" yet unforgettable time. Being a first-timer, we were all very excited and spent a lot of time following the negotiations, staying up until 2 or 3 AM, and then continuing the next day. Looking back, it was truly a passionate and memorable period. At this year's Madrid conference, seeing several friends post about their first COP experience, I could deeply feel their excitement.

The influence of the UN Climate Conference has always been significant. For individuals, attending the conference broadens their horizons. For companies, it offers a rare opportunity to showcase their efforts, viewing it as the highest stage in the field of climate change and low carbon. Many company executives light up when discussing the possibility of showcasing at the UN Climate Conference. In this sense, the conference's influence, meaning, and value are substantial and necessary to continue.

The Personal Carbon Footprint Dilemma of Gore, Messi, and Solheim

Despite the positive influence of the UN Climate Conference, long-term inefficient negotiations, significant economic investment, and the conference's own carbon footprint have become increasingly prominent. Recently, I noticed an interesting topic about public figures who advocate for environmental protection being criticized for their high personal carbon footprints.

For example, former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has been questioned for his high electricity consumption. His home uses enough power for an average American household for 21 years, with the electricity used to heat his swimming pool equivalent to the annual consumption of six average American households. Gore's team responded that he achieves carbon neutrality by purchasing green energy; the electricity source is high-emission, which he cannot control; and his house is used for both living and working. Are these explanations sufficient?

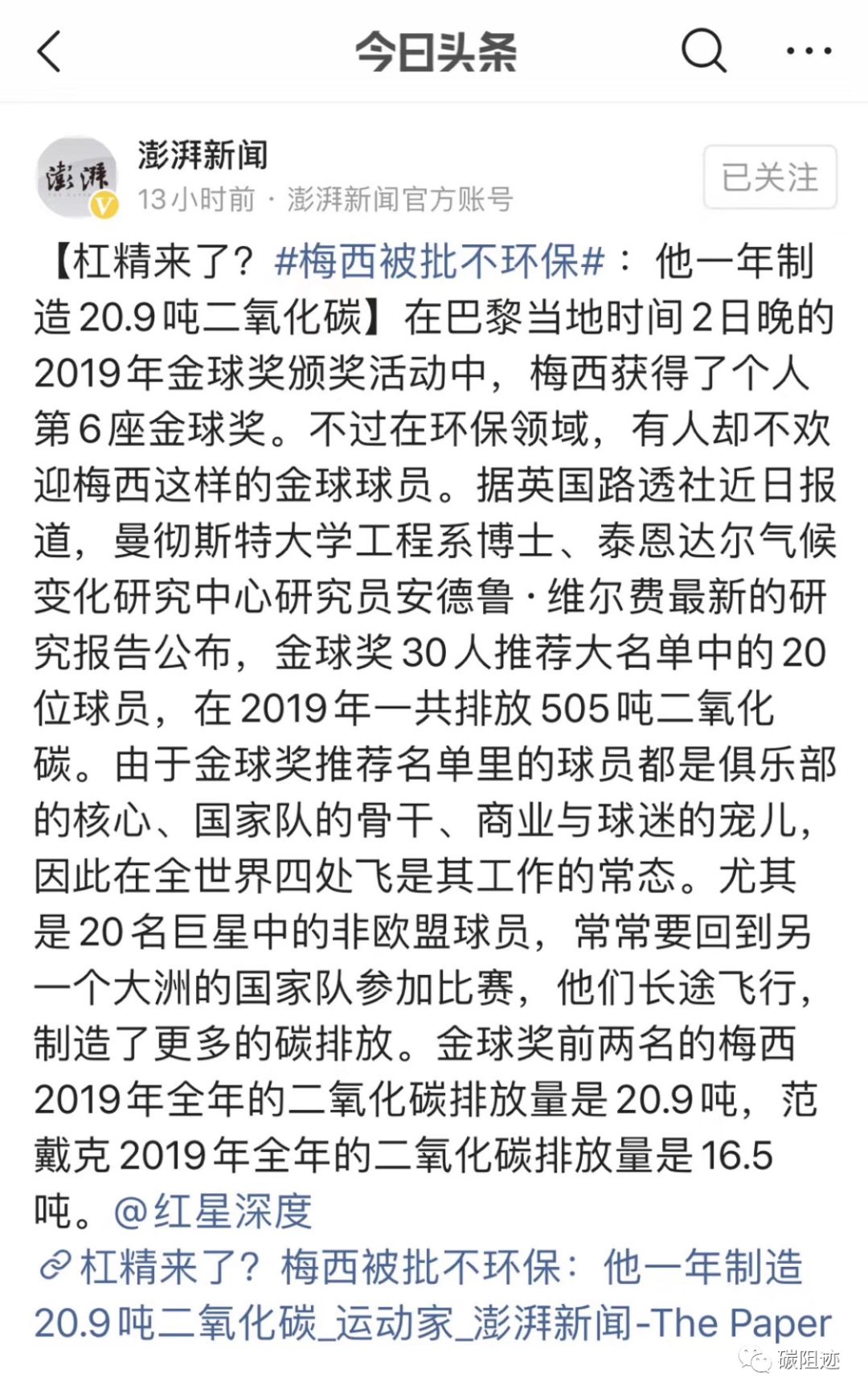

World Footballer of the Year Lionel Messi has also been criticized by environmentalists for his excessive carbon footprint, mainly due to frequent flights for matches (the article reveals that Messi's annual personal carbon footprint is 20 tons, which is actually conservative, as a single international round-trip flight can produce around 3 tons of carbon, and Messi likely flies more than six times a year).

Former UNEP Executive Director Erik Solheim resigned last year partly due to excessive travel, travel expenses, and the resulting carbon footprint.

Each attendee at COP carries a 3-ton carbon footprint to participate in the 1-2 week UN Climate Conference. Is this the right approach to solving climate problems? Could there be better solutions?

The common issue with these cases is how to correctly view the high carbon footprints of public figures who have a positive influence on society. Their work and activities do raise awareness about environmental issues and prompt action. If we consider the "small sin for a greater good" argument, this should be encouraged. Public figures can break through the boundaries of niche topics in ways insiders cannot, as seen with Zheng Shuang's participation in COP25, which attracted substantial media attention and fan engagement. Compared to their positive impact and the momentum they create, the personal carbon footprints of figures like Gore and Messi are relatively minor. However, as equal citizens, reducing one's carbon footprint remains an important task and challenge.

A consensus needs to be formed to objectively assess the normal carbon footprints of different regions and professions. For example, residents in major cities typically have higher carbon footprints than those in less developed areas, but encouraging a return to less developed areas or a primitive lifestyle is impractical. Different jobs require different daily activities. We need to establish standards to measure personal carbon footprints based on region and profession, rather than using a one-size-fits-all approach based on national or global averages.

This issue has puzzled me, but a conversation with a senior in the low-carbon field provided some insights. He believes that low carbon should not mean lowering quality of life, which contradicts economic development. For transportation, he lives in the outskirts of Beijing and sets a standard: if he needs to enter the Third Ring Road, he drives to the nearest subway station and takes the subway into the city. He avoids peak hours and schedules meetings in the afternoon to reduce traffic and save time, thus reducing his carbon footprint. Unnecessary travel is avoided, and phone or video calls are preferred. Despite these efforts, his annual carbon footprint still exceeds 15 tons (due to frequent international and domestic travel), much higher than the Chinese average. In this case, the reasonable solution is to minimize personal carbon footprints and offset unavoidable emissions through tree planting or other means.

Regarding how individuals can reduce their carbon footprint in daily life, my team recently collaborated with the International Platform for Urban Carbon Peak to analyze the low-carbon potential of urban residents. We explored feasible ways to reduce carbon emissions in key areas of daily life, including clothing, food, housing, transportation, and consumption.

Clothing: By reducing clothing purchases, renting clothes, and choosing brands with emission reduction goals, each person can achieve over 30 kg of carbon reduction in 2020 and over 80 kg by 2030.

Food: By adopting a meatless day per week, reducing meat consumption, and practicing the clean plate campaign, each person can achieve over 800 kg of carbon reduction in 2020 and over 900 kg by 2030.

Housing: By conserving electricity, choosing renewable energy sources, and using energy-efficient appliances, each person can achieve over 200 kg of carbon reduction in 2020 and over 400 kg by 2030.

Transportation: By driving one less day per week, using more electric vehicles, and opting for trains over flights for long-distance travel, each person can achieve nearly 200 kg of carbon reduction in 2020 and over 400 kg by 2030.

Consumption: By reducing the use of disposable items, choosing green packaging, and practicing waste sorting, each person can achieve nearly 20 kg of carbon reduction in 2020 and over 30 kg by 2030.

In summary, for citizens in large cities, achieving a total carbon reduction of over 1 ton per year in 2020 across clothing, food, housing, transportation, and consumption is not particularly difficult. As the proportion of renewable energy increases and public awareness of low-carbon living strengthens, by 2030, each person can achieve a carbon reduction of over 2 tons per year in daily life.